|

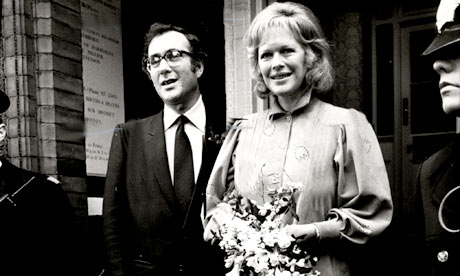

| In 1980, Pinter married his second wife, the historian Lady Antonia Fraser, at Kensington registry office. "He was a great man, and it was a privilege to live with him for over 33 years," said Fraser in a statement to the Guardian on Christmas day. "He will never be forgotten." |

Harold Pinter and Antonia Fraser: a perfect match

Antonia Fraser's memoir of her life with Harold Pinter reveals the warmth, passion and romance in their marriage. And, says his biographer Michael Billington, it shows he was not always in a bad temper

Do revelations about Pinter's private life shed light on his work?

Do revelations about Pinter's private life shed light on his work?

Harold Pinter and Lady Antonia Fraser photographed in 1985. Photograph: David Montgomery/Getty Images

Diaries and journals are always compulsive affairs. I defy anyone to open Pepys, Boswell or the Goncourts at any page and not carry on reading. And, on a theatrical level, Peter Hall's Diaries offer the best ever account of the hazards of running a theatre. But Antonia Fraser's memoir of her life with Harold Pinter, Must You Go?, is extraordinary by any standards. Based on the diaries she kept during her 33-year-long relationship with the dramatist, it is simultaneously a love story, an intimate portrait of a great writer and an exercise in self-revelation.

I should, from the outset, disclaim any objectivity. As Pinter's biographer, I was given rare access to the man himself and I'm happy to say remained on friendly terms with him right up to the end.

I was amused, however, to be told by Antonia, shortly after Harold's death, that my book was never expected to happen. In order to fend off another would-be biographer, Harold and Antonia concocted a plan whereby they told the persistent writer that I had been asked to do the authorised version. They both assumed I'd be far too busy to accept and were astonished when I said yes.

Reading Antonia's book, I was also intrigued to discover that as long ago as 1980 they had discussed a future biographer ("What a morbid subject," said Harold) and decided, very astutely, that Ronnie Harwood would be the man for the job.

Inevitably, my relationship with Harold was complex. I had to get close enough to him to write the book while remaining sufficiently detached to review his work. I can truly say that Harold and I hardly ever fell out: only once did he show irritation. That was when, on the opening day of a Pinter festival in New York in 2001, I pushed a note under his hotel door about criticism from Germany of his attack on the trial of Slobodan Milosevic for war crimes. That evening in the bar I asked whether he got my note. He simply growled in response.

But that was a rare event. During all my contact with Harold and Antonia, I was offered unwavering support. Antonia talked candidly about Harold for my book, gave me a mass of new information about his family's origins (revealing they were east European Ashkenazic rather than Portuguese Sephardic Jews) and has gone on being a good friend. I was more touched than she can have realised when she asked me to coach her granddaughter, Stella Powell-Jones, in reading one of Pinter's love poems for the family funeral. "Normally," said Stella, "I came to Grandad himself for this kind of help."

So reading Antonia's book puts me in a strange position. I learned much that was new and had other impressions confirmed. But the dominant feeling I got was that the love of Harold and Antonia, which was passionate and intense, was based on the mutual force of their characters. Early on, just after their affair had got under way in 1975, Antonia was warned by her brother, Thomas: "You have a special problem. You are a woman and a strong character yet you want your husband to be stronger. Women with strong characters who want to dominate are always fine because there are plenty of weak men around. Also plenty of strong men for weak women. But yours is a special problem." Actually, Antonia concludes, "He's quite right in a maddening way."

What may, initially, have seemed a problem was, arguably, the key to the relationship. If Harold was an irresistible force, Antonia could also, on occasion, be an immovable object. And one of the delights of the book is reading about their sometimes tempestuous political disagreements. On the matter of Milosevic, Antonia argued, rightly in my view, that it was legitimate to try him as a war criminal even if others were not similarly arraigned. And, when Harold claimed that the US was the world's most barbarous empire, Antonia reasonably argued that the Nazis or Pol Pot might have superior claims.

But, although Harold and Antonia often had vehement political arguments, they vowed that they would not, as in the Bible, "let the sun go down upon our wrath".

I was not totally surprised by this. But the book dispels the popular myth that Harold was the eternal grump and Antonia always the soothing diplomat. Antonia, although she has a great capacity for outward calm, comes out of the book as an independently strong character and a fierce champion of women in public life: one that led her to vote, however madly, for Margaret Thatcher in 1979 and to warm to Cherie Blair even when Harold was branding her husband a war criminal.

The book should also put to bed for ever the idea that Harold spent all his life in a towering temper. In matters of the heart, he was a total romantic: one who arranged for the first house he and Antonia shared, in Launceston Place, to be strewn with banks of flowers on the day they moved in. "August 17, 1975. He took my hand and led me into the drawing room. Lo! A vast arrangement of foxy lilies and other glories in the window and another on the mantelpiece, a huge arrangement of yellow flowers in the pink boudoir . . . I shall never forget them. Or Harold's expression. A mixture of excitement, triumph and laughter."

'I'm not just sitting here waiting to die'

He was also – and this really will shock some – capable of self-mockery. There's a vivid account of Harold exploding with laughter when he saw Ayckbourn's Bedroom Farce. The reason? He saw in the frustrated rage and impotence of Derek Newark as a suburban husband an echo of himself.

If anything in the book surprised me, it was how accommodating Harold was towards Antonia's Catholicism: something I signally failed to take on board in my own book on Pinter. I knew – because he told me many times – that Harold had abandoned the Jewish faith after his barmitzvah at the age of 13. What I learned from Antonia's book is that in 1990, 10 years into their marriage, she persuaded him to have a ceremony of validation in an upstairs chapel at Farm Street. It helped that Father Michael Campbell Johnston, who conducted the ceremony, was a leading supporter of liberation theology in Latin America. But, when it came to the actual service, Harold joined in vocally and enthusiastically celebrated the idea of a fruitful life. This doesn't mean Pinter was innately religious. But it does prove, as Antonia claims, that "he had a deep sense of the spiritual".

Time and again, in fact, the book draws attention to the complexity, and even contradictoriness, of Pinter's nature. I nearly fell out of my chair when I read Antonia's comment, made in 1977, that Harold "resents any effort to link his plays closely to a particular incident in his past". It was certainly true that Harold, who was writing Betrayal at the time, was anxious that it should not be seen as a literal account of his affair with Joan Bakewell, the existence of which I revealed, nearly 20 years later, in my biography.

Yet while Harold was never a purely autobiographical writer, I found that his imagination was invariably triggered by a memory of some past event. The Caretaker was born out of an image that stuck in Harold's mind when he and his first wife, Vivien, were living in a modest flat in Chiswick High Road: one day he paused on the stairs and looked in a room to see the tramp who had taken up residence rifling through a bag, silently watched by his benefactor. And, while The Homecoming is a universal play about family life, it had its origins in the story of one of Harold's Hackney friends who for years kept his marriage to a Gentile girl a secret from his Jewish family.

Even more surprising than Harold's disavowal of his work's personal origins is the record of an evening in 1977 spent with Samuel Beckett and his close friend, Barbara Bray. Since Beckett hardly ever went to the theatre, Harold acted out for him the Simon Gray piece, Close of Play, that he was directing at the time. This prompted a discussion in which Bray claimed that everything in art is political. To which Harold replied, vehemently, "Nothing I have written, Barbara, nothing, ever, is political."

This hardly squares with Pinter's later assertion that early plays such as The Birthday Party and The Hothouse were driven by a strong political motive. But, while Pinter-sceptics may seize on this as proof of his inconsistency, I suspect it simply proves Harold's dislike of aesthetic dogma. I can actually picture him bubbling with resentment at being told by Bray what art has to be.

But, if Antonia's book sometimes makes one's eyebrows start upwards in surprise, it also offers the most vividly intimate portrait we're ever likely to have of the real Harold Pinter. It records the energy and exuberance for living that burned off him and that made him so attractive to male and female friends alike. It describes his passionate love of England: its cricket, its countryside, its natural beauty and its historic regard for liberty. It was precisely because he saw that liberty being curtailed and eroded that he became such a ferocious opponent of successive governments. Indeed, the book pins down the embattled despair that Harold sometimes felt in later years as his sense of the world's injustice coincided with his own declining health. But he never gave up. As he said when about to perform at the National in his own sketch, Press Conference, while wrestling with chemotherapy for his cancer, "I'm not just sitting here waiting to die."

This for me sparks a memory of Harold in his later years when he was afflicted by cancer of the oesophagus and pemphigus: his consideration for others. It may seem a relatively trivial anecdote, but I rang Harold one day when I had been summoned to hospital for an endoscopy on account of sharp internal pains. The literature I got from the hospital implied that there was no need for an anaesthetic while a length of tube was stuck down your throat: real men, it suggested, didn't need such things. Seeking advice from Harold, I was instantly told, "Don't be such a bloody fool – of course you must have an anaesthetic." Not only that. At a time when Harold was weighed down by his own, far greater, medical problems, he rang up immediately after the endoscopy to ensure that all was well. That, for me, was a measure of the man's kindness and generosity.

That day, anyone who crossed his path was in danger

All this – and much more – comes out in Antonia's memoir. It is not the story of a saint. Everyone who knew Harold was aware that, on occasions, his anger was disproportionate to the event: I once heard him, at a Dublin dinner party, going hell for leather at some poor chap who had guilelessly suggested that Johnson was a greater figure than Swift. On another occasion in Leeds, admittedly when he was severely ill, he tore into some local academic whom he mistakenly thought had laughed at his reminder that the American president was, like many tinpot dictators, also the military commander-in-chief. That was an evening when anyone who crossed Harold's path was in danger.

But what you get from the book is a portrait both of an inordinately fascinating, richly complex man and writer ("the half of Harold which is not Beckett," says Antonia, "is Hemingway") and of a genuine "marriage of true minds".

Although the book is free from personal vanity, it also reminds one just how much Harold owed to Antonia. Even with her own career to pursue, she was always on hand to advise, support and encourage: it was Antonia who tentatively suggested – correctly as it turned out – that there was a scene missing in the first draft of Betrayal ("December 31, 1977: Harold very cross and went for a walk round Holland Park. Came back and wrote the scene. It was brilliant and not at all what I had asked for of course") and who recommended that Harold's last play, Celebration, should be paired with his first, The Room.

It's a testament to the resilience of Harold and Antonia's relationship that it overcame both the insane press hysteria that accompanied their affair and the initial doubts of Antonia's parents. I am hardly an impartial witness. But I would say that if this remarkable book proves anything, it is that marriage thrives when it is a partnership of equals and that Harold and Antonia, as a pair of strong-willed and impassioned romantics, were that rare thing: a perfect match.

Read also